Co-Ownership Profit Split Calculator

Calculate Your Fair Profit Split

Contribution Breakdown

Your Equity Breakdown

Equity-Based CalculationTotal Equity Contributions

You: $0

Co-owner: $0

Total: $0

Your Profit Share

Your share:

Co-owner share:

Total profit: $0

Contribution Summary

When you buy a home with someone else, you’re not just splitting the rent or the mortgage-you’re splitting the returns. But how much do co-owners actually make? It’s not as simple as dividing the sale price by two. The truth depends on who put in what, how the agreement was written, and what the market did while you lived there.

Co-ownership isn’t just about splitting bills

Many people think co-owning a home means splitting everything 50/50. That’s only true if both people paid exactly half the deposit, covered half the mortgage, and did equal repairs and upgrades. In real life? That rarely happens.

Take two friends in Auckland who bought a three-bedroom house in Mt. Roskill in 2021. One put down $120,000-80% of the deposit. The other put in $30,000. They agreed to split monthly costs equally because they both worked full-time. But when they sold in 2025, the house went for $1.1 million. The original purchase price was $850,000. After fees and paying off the $500,000 mortgage, they had $480,000 left.

Here’s where it gets messy: if they split that evenly, the person who paid only 20% of the deposit got half the profit. That’s not fair. That’s not how most legal agreements work. Most co-ownership contracts tie profit share to equity contribution, not income or living expenses.

How profit is actually divided

There are three common ways co-owners split money when selling:

- Equity-based split - Profit is divided based on how much each person contributed to the purchase price and major improvements.

- Equal split - Everyone gets half, no matter what they paid in. This is rare and usually only works between family members with strong trust.

- Hybrid model - One person gets their initial investment back first, then profits are split evenly. This protects the bigger investor but still rewards shared effort.

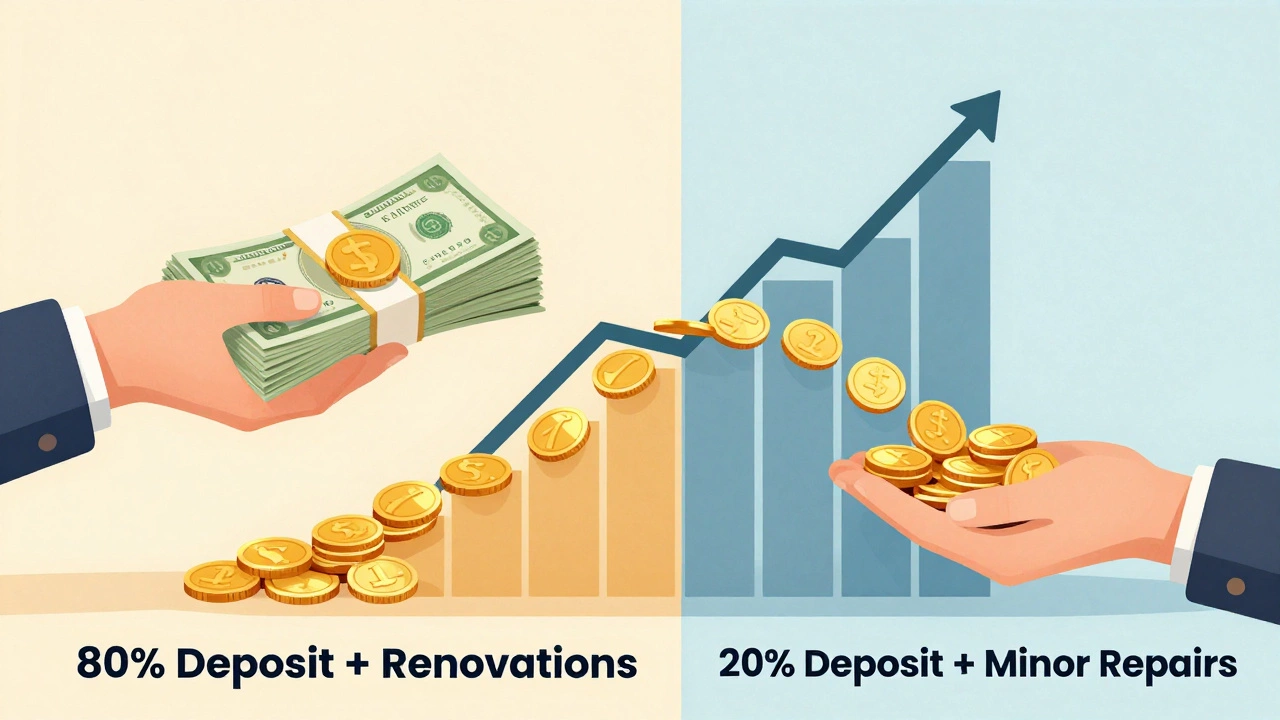

The equity-based model is the most common in formal agreements. In the Mt. Roskill example, the first person contributed 80% of the deposit. They also paid for a new kitchen ($18,000) and a roof replacement ($12,000). The second person paid for painting and minor fixes ($5,000). Total equity contributions: $120,000 + $18,000 + $12,000 = $150,000 for Person A. Person B: $30,000 + $5,000 = $35,000. Total equity: $185,000.

Person A’s share: 150,000 ÷ 185,000 = 81.1%. Person B: 18.9%. Of the $480,000 profit, Person A gets $389,280. Person B gets $90,720. That’s how it should work. And that’s how courts usually rule if it goes to dispute.

What co-owners actually earn annually

Most people don’t sell right away. They live in the home for years. So what’s the annual return?

Let’s say you co-own a home with someone and rent out half of it. You live in one bedroom, your co-owner lives in another, and you rent the third. In Auckland, a three-bedroom house in a decent suburb rents for $900-$1,200 per week. If you split the rent evenly, that’s $450-$600 per person per week. That’s $23,400-$31,200 a year in rental income-before taxes, maintenance, or rates.

But here’s the catch: if you’re living in the home, you’re not earning rent from your own room. So the real income is only from the rented room. That means $13,000-$17,000 per year in net rental income, assuming $500/month in repairs and $300/month in rates.

Now, if you’re not renting at all-just living there-your "earnings" come from equity growth. In Auckland, property values rose 12% in 2023, 8% in 2024, and 5% in 2025. That’s a compound gain of about 26% over three years. If you put in $100,000 as your share of the deposit, your equity grew by $26,000. That’s $8,667 per year in paper gains. But you can’t spend it until you sell.

What co-owners don’t make (and why it matters)

Co-owners don’t get tax refunds just because they own property. In New Zealand, you don’t pay capital gains tax on your main home-but you do if you sell a co-owned investment property within 10 years of purchase, unless you meet the bright-line test exemption.

Also, co-owners don’t automatically get access to KiwiSaver first-home withdrawals unless they meet the criteria: they haven’t owned property before, they’ve contributed for at least three years, and the home is their primary residence. If you’re buying with someone who already owned a home, you might be eligible-but they’re not.

And here’s something no one talks about: co-ownership can cost you more than it saves. Legal fees for a co-ownership agreement? $1,500-$3,000. Property manager if you rent out a room? $1,000-$1,800 a year. Disagreements over repairs? Time, stress, and sometimes lawyers.

Real examples from real co-owners

In Wellington, a couple bought a flat in 2020 as co-owners. One was a teacher, the other worked freelance. They each put in $75,000. The flat sold for $780,000 in 2025. Mortgage paid off: $420,000. Fees: $45,000. Profit: $315,000. Split 50/50: $157,500 each. That’s a 210% return on their initial investment. They used their share to buy separate homes.

In Christchurch, two sisters co-owned a house. One moved out after two years and rented elsewhere. The other stayed. They agreed the staying sister would pay all bills and maintenance. When they sold, the one who moved out got 60% of the profit because she’d paid 60% of the deposit. The staying sister got 40%, even though she’d lived there and paid for everything for three years. No one was happy. That’s why written agreements matter.

How to make sure you’re not getting ripped off

If you’re thinking about co-owning, here’s what you need to do before signing anything:

- Get a co-ownership agreement drawn up by a lawyer. Don’t use a template from the internet.

- Define exactly how contributions are tracked: deposit, mortgage payments, renovations, rates, insurance.

- Decide how profits are calculated: only initial equity? Or include improvements?

- Agree on what happens if one person wants to sell early.

- Specify who pays for what if one person moves out but stays on the title.

- Include a buyout clause: how the property is valued, how the buyout payment is structured.

Most people skip this step because it feels awkward. But it’s the difference between walking away with $100,000-or $0.

Who makes the most from co-ownership?

The person who puts in the most money upfront usually makes the most. But not always. The person who manages the property, pays for upgrades, and keeps the place in good shape can earn more over time-even if they put in less cash.

Co-ownership works best when both people are clear, honest, and committed to the same goal. It’s not a shortcut to wealth. It’s a partnership that needs structure, trust, and a paper trail.

If you’re considering it, talk to a financial advisor who’s handled co-ownership cases. Don’t rely on what your friend did. Every situation is different. And if you’re unsure? Wait. Buying a home is big enough without adding someone else’s money, expectations, and drama into the mix.

Do co-owners pay tax on their share of the profit?

In New Zealand, if the co-owned home is your main residence, you don’t pay capital gains tax when you sell. But if it’s an investment property and you sell within 10 years of buying, you might owe tax under the bright-line test. The tax is based on your share of the profit, not the total sale price. Always check with Inland Revenue or a tax advisor.

Can you co-own a home with someone who isn’t family?

Yes. Many people co-own with friends, colleagues, or even strangers through shared equity schemes. But the more unrelated the people are, the more important a legal agreement becomes. Without one, disputes over repairs, rent, or selling can end up in court.

What happens if one co-owner stops paying the mortgage?

If one person stops paying, the lender can still pursue both names on the loan. The other co-owner is legally responsible for the full amount. That’s why it’s critical to have a written agreement that outlines what happens in this case-like a buyout option or a requirement to sell. Without it, you could lose your home.

Is co-ownership better than renting?

It depends. If you can afford your share of the deposit and mortgage, co-ownership builds equity over time. Renting doesn’t. But if you’re not sure you’ll stay in one place for five+ years, renting gives you flexibility. Co-ownership ties you down. You also need to be ready to handle repairs, disputes, and market swings.

Can I use KiwiSaver to buy into a co-owned home?

Yes-if you’re a first-time homebuyer and haven’t owned property before. You can withdraw your KiwiSaver savings (plus government contributions) to use as part of your share of the deposit. But your co-owner can’t withdraw theirs if they’ve owned property before. Make sure your agreement reflects who’s eligible and how the funds are used.